Arriving late, my schedule was disrupted by Hong Kong’s recent bad weather, and I finally got around to reading the popular novel Normal People. Don’t blame me, even though it was published in 2018 and became popular in 2019, Hongkongers were so busy then. I loved this novel, and the leading actors in the adapted TV series were very appealing, so I decided to watch that as well.

The novel and series complement each other

I wanted to write a spoiler-free review of Normal People, but I couldn’t. Instead, I’ll try to confine all the spoilers to this section, so readers who haven’t watched or read can consider skipping it.

Critics highly praise Normal People, seeing it as a future classic. Many celebrities, including former U.S. President Barack Obama, who included it in his 2019 best books list, have recommended it. The story is set in Ireland between 2011-2015 and revolves around high school and university students, mostly from the millennials. I’m not familiar with the local culture and don’t fully understand the millennial generation. I also lack literary training and seldom read foreign novels. So, I can only relate from my own youth memories, aligning with the author’s and protagonists’ political views and my own past confusion about being ‘abnormal’, which made me fall in love with this novel.

The author, Sally Rooney, is also from West Ireland and studied English at Trinity College, Dublin. Born in 1991, this is already her second novel. The writing in Normal People is concise and unpretentious, so native Chinese speakers can try reading the original version. The story revolves around rich girl Marianne and poor boy Connell from high school to university. At a glance, the plot sounds cliché, but it seamlessly integrates themes of love, society, family, growth, social interactions, literature, politics, etc.

In the past, when it came to adapted works, either I hadn’t read the original text, or I hadn’t watched the movie or series. Otherwise, the adaptations were so different that they were incomparable. It’s a unique experience for me to finish reading a novel and immediately watch its closely adapted series, especially when both are so alike. Because the series stays true to the story and dialogue from the original, I often knew the characters’ next lines when watching. Even though this took away some surprises, it allowed me to focus more on the details of the filming and the performances of the actors. Instead of diminishing the viewing pleasure, it made the text and performance complement and strengthen each other, making the experience more profound.

The series features Daisy Edgar-Jones as Marianne. I had previously seen her performance in Where the Crawdads Sing as the ‘marsh girl,’ and she left a good impression. As for Paul Mescal, who plays Connell, his restrained performance in Aftersun was particularly powerful. Just looking at the cast was promising, and after watching the performances, I became even more fond of both actors. If I had to nitpick, I’d say that Marianne’s high school portrayal was too beautiful, even more so than her appearance in later episodes with heavy makeup, which didn’t match the novel’s description of her as an oddball. Of course, I’ll forgive the production team for this.

While the series produced by the BBC is faithful to the original work, it primarily focuses on the on-again, off-again relationship of the two main characters. The literary and societal themes mentioned in the novel were mostly omitted in the series, making it more about the pure depiction of their relationship. It lacks the groundwork on how the pair, as soulmates, came to be, giving a somewhat abrupt feeling of their relationship heating up (as I said, I don’t quite understand the millennial generation). However, the pairing of a handsome man and a beautiful woman alone is enough to explain how their affection for each other grew. With numerous intimate scenes added, who would further question the reasons behind their bond?

But I’m not saying the series is attractive just because of its ‘love scenes’ (though they’re indeed well-executed). In fact, within the six-hour series, the two most striking scenes that left a deep impression on me are quite simple. One is when the two uncontrollably embrace at a schoolmate’s funeral, translating a mere few lines from the novel into a poignant performance that gives one goosebumps. The other is when Marianne, trying to comfort Connell who’s suffering from depression, says ‘Carry me over to your bed,’ and Connell places his laptop beside his bed, allowing Marianne, who’s pulling an all-nighter for her studies from afar via Skype, to accompany him to sleep. This scene, a brilliant addition not present in the novel, truly stands out.

I don’t know what’s wrong with me. I don’t know why I can’t be like normal people.

Marianne

Ordinary and Normal

Though I’m worlds apart from Connell’s tall, handsome stature, excellent grades, and athletic prowess, I am intimately familiar with his feeling of being out of place upon entering university. I felt the need to overcome social anxiety, but once I arrived at social events, I often wanted to escape immediately. I wanted to believe that I was just a normal person, yet I couldn’t engage in group topics or interests.

I thought it was just me lacking certain skills during my university years, extending maybe to the early days after graduation. I hoped that by midlife, I’d be entirely self-assured, not minding others’ opinions. For a while, it seemed I had achieved this. However, it turned out I only felt that way because daily social interactions in a business environment didn’t touch upon deep-seated values. It was only after 2019, when all contradictions surfaced, that I realized I never truly mastered social skills.

After years of the pandemic, the world dubbed the new social paradigm the ‘new normal.’ Only Hongkongers know that what happened here was ‘new normal ^2’, with shifts in ideology and presentation methods at the same time. Everything changed. I, who once thought I was getting the hang of navigating social situations, regressed along with Hong Kong, reverting to past behaviors or even worse. If there’s any progress, it’s only that different life stages allow me some conditions to say ‘no’ to certain social situations.

While searching for the Normal People series, I found that many mainland Chinese websites and reviews translated the title as “普通人” (Ordinary People), differing from the official Chinese version which translates as “正常人” (Normal People), both in Taiwan and mainland China. This might be purely due to Baidu’s influence without any cultural significance, but it got me thinking: If I were the translator, would I choose “正常人” (Normal People) or “普通人” (Ordinary People)?

Without consulting a dictionary or authoritative source, based on my understanding of Chinese, “正常” (normal) has a neutral-to-positive connotation, while “普通” (ordinary) has a neutral-to-negative one. To illustrate: if I said you were “不普通” (extra-ordinary), it typically means you have unique qualities; but if I said you were “不正常” (abnormal), it might mean you’re odd enough to be sent to a “Center for Abnormal Human Studies”. Unlike “ordinary”, “normal” implies a certain standard or expectation, suggesting it’s “better to be within this range.”

Given this interpretation, translating the work as “正常人” (Normal People) is more apt. After all, the story revolves around Marianne and Connell’s quest to be recognized as “normal people”, not just as “ordinary people”.

We didn’t have a lot in common, like in terms of interests or whatever. And on the political side of things we probably wouldn’t have had the same views. But in school, stuff like that didn’t really matter as much. We were just in the same group so we were friends, you know.

Connell

Defining the Boundary of Normal

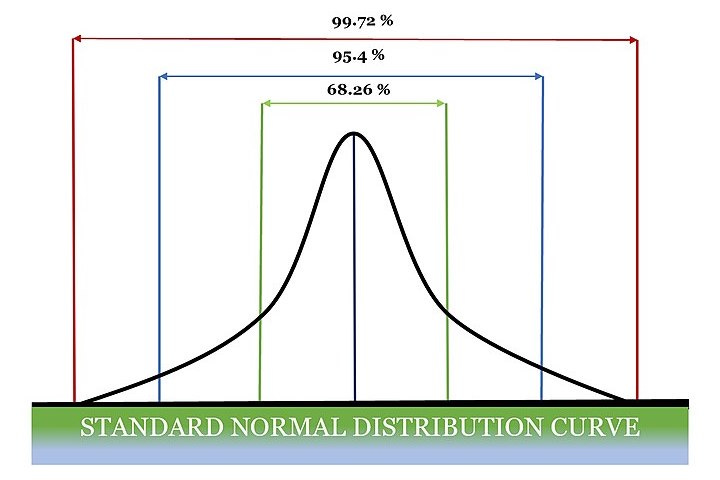

In statistics, there’s a concept known as the normal distribution, which is widely observed in probability distribution. When plotted, it resembles a bell, hence the term “bell curve.” The highest point is in the middle, and it tapers off on either side. Within one standard deviation of the mean, you cover 68% of the data, within two standard deviations, 95%, and within three, 99.7%.

To define “normal” quantitatively, one could use the normal distribution and consider individuals within one standard deviation as “normal.” Those within one to two standard deviations, two to three standard deviations, or beyond three are respectively viewed as slightly abnormal, very abnormal, and extremely abnormal. The Cosmos blockchain has a similar setup, where any transaction securing over 66.7% of votes is deemed “correct” and accepted as a consensus. All other transactions are rejected. This entire process is devoid of value judgment. However, ordinary doesn’t mean normal, societal consensus isn’t like transaction logging, and life is not math. Many aspects are qualitative rather than quantitative. Even if quantifiable, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the middle of the normal distribution is, in fact, “normal.”

In university, I took a course called the “Sociology of Crime and Deviance” which discussed crime and deviant behaviours. It mentioned the “function” of deviance is to clarify social norms (the word “normal” is derived from “norm”). This was a revelation for me; on one hand, sociology provided insights into understanding the world, while on the other, it seemed cruelly indifferent to individuals.

“Normal people” often hold societal norms in high regard, unaware of its ever-evolving nature. Take gender and marriage norms as examples. There are many outdated practices: couples used to prioritize matched socio-economic backgrounds, premarital sex (especially for women) was taboo, shotgun marriages were scorned, women were expected to bind their feet and solely focus on supporting their husbands and raising children, and homosexuality was deemed heretical. All these norms, once considered sacrosanct, have been shattered in just over a century. Each change didn’t come from a divinely enlightened ruler but arose because various “deviants” sought justice, endured ridicule, faced oppression, and forced “normal people” to articulate their arguments more clearly. This gradually redefined various “abnormals,” clarified societal norms, and implemented legislation to protect minorities.

Ever since I embarked on the project to bring books to the Hong Kong DeCentral Library (HKDCL), I have received numerous messages, all kindly cautioning me to be careful. Responding to these well-meaning concerns is even harder than facing open criticism. If I could be as brutally honest as Marianne in high school, not minding how others might feel, I would love to say: If you believe that I am thoughtful in my actions, please don’t express your concern in this way. Caring for an “abnormal person” from the standpoint of a “normal person” not only doesn’t help the situation but also intensifies my feelings of isolation. If you genuinely care, better to support my actions than offer words.

The primary goal of HKDCL is to archive the books and reports deemed “abnormal” by the government. This top-down classification is even more unfounded than the old-fashioned societal norms mentioned earlier. However, just as societal norms can’t be challenged without the presence of outspoken “deviants,” if citizens don’t buy, read, collect, sell, and promote the books that public libraries have removed, these books will essentially be banned, fading away on their own. It’s only when enough people show concern for these books and question the reasons behind their prohibition that the government and the courts will be pressured to clarify the boundaries of censorship. They would be forced to transform a vast, ambiguous “red zone” into a relatively clear “red line” (even if it remains unreasonable), allowing as many books, authors, and publishers as possible to return to normalcy.

Marianne’s classmates all seem to like school so much and find it normal. To dress in the same uniform every day, to comply at all times with arbitrary rules, to be scrutinised and monitored for misbehaviour, this is normal to them. They have no sense of the school as an oppressive environment.

In 2018, an overwhelming majority in Ireland’s national referendum voted to repeal a national anti-abortion act that had been in place for 35 years. Sally Rooney, who supported the referendum, said in an interview with the New York Times: “I felt incredibly happy to feel normal. It was like, ‘Oh, this is amazing. I feel so at home, walking down the street, seeing people who probably agree with my opinion.’”

Hong Kong people, do we possess the strong will needed to someday transform our “abnormal” beliefs into a norm that neither society nor the regime can find excuses to suppress?

Leave a Reply